A 2024 election pop quiz. Who was the most famous—not to mention the most entertaining—third-party presidential candidate in the history of the United States? The answer is not comedian Pat Paulsen (who ran repeatedly from 1968 onward). Not Ross Perot (in ’92 and ’96). Not Ralph Nader, Jill Stein, Kanye West, or even the maddening, bewildering Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

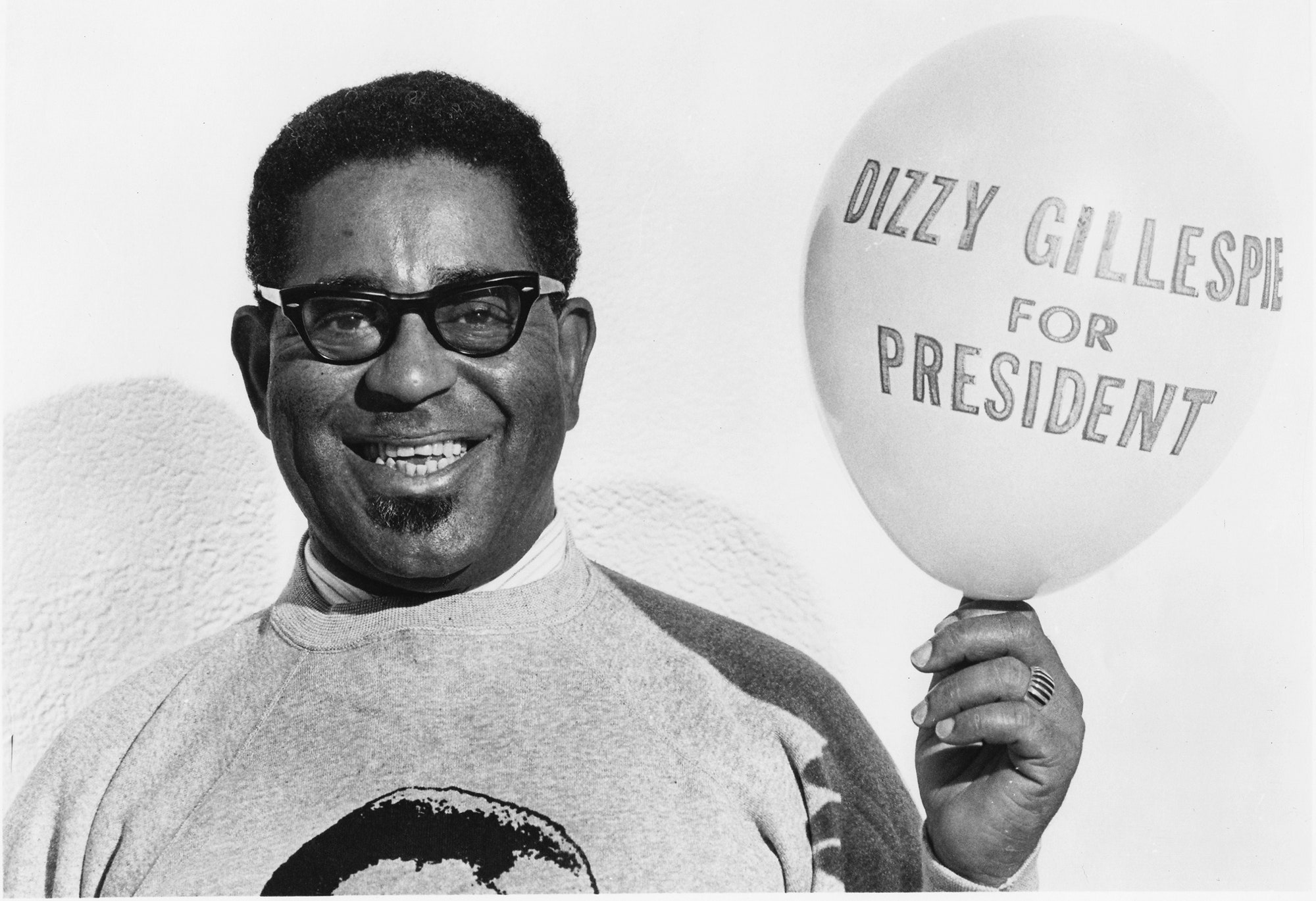

The answer is John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, the legendary jazz trumpeter, composer, and innovator, who ran as an independent candidate in 1964 against incumbent Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson and far-right Republican contender Barry Goldwater.

Through his more than 50-year career, Gillespie was celebrated not only as a great jazz musician—a true giant of the genre—but, like Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller before him, a masterful entertainer. In fact, as the contemporary jazz pianist Bill Charlap observes, “Dizzy was so funny up onstage that it often obscured what a brilliant and amazing musician he was.” The 93-year-old saxophone colossus Sonny Rollins, who worked with Dizzy frequently, agrees, telling me that the public regarded Gillespie much as they did Armstrong, “as an entertainer, a comedian almost, as well as a musician.”

In his memoir, To Be, or Not…to Bop, Gillespie states that his presidential campaign “started largely as a result of the March of Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 and the Newport Jazz Festival.” However, he was actively campaigning—with buttons and banners, no less—at least as early as February of that year at the Blackhawk nightclub in San Francisco, well before Martin Luther King Jr.’s, historic march of August 1963 was even conceived. “It wasn’t just a publicity stunt,” he later wrote in his memoir. “I made campaign speeches and mobilized people. I meant to see how many votes I could get, really, and see how many people thought I’d make a good president.”

Gillespie’s politics made it onto the bandstand as well. For much of 1963, his sets were a combination of his regular modern jazz performances, including such original standards as “A Night in Tunisia” and “Con Alma,” interwoven with semiserious campaign rhetoric. By September, the campaign—by then officially managed by Jean Gleason, wife of Ralph J. Gleason, the jazz critic who later became a founding editor of Rolling Stone—was in full swing. That month, when Gillespie played the sixth annual Monterey Jazz Festival, Down Beat reported that not only was “Dizzy for President” merchandise being given away and sold throughout the festival, but Gillespie and Gleason had already gathered more than 1,000 signatures on a petition to officially put him on the ballot in California.

The legendary bassist Ron Carter, now 87, was a member of Miles Davis’s great quintet of the period, and also played Monterey that year. He says of the Gillespie campaign, “We all treated it like it was a lark. As individuals we were often asked to play to raise awareness of presidential candidates. Dizzy’s ‘candidacy’ was to let people know we didn’t just play music—we had our eye on who the next president would be.”

A few weeks later, the candidate was asked to speak at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, mostly fielding questions from the crowd that had been written in advance and were then read by Gleason. Gillespie spoke authoritatively on such subjects as whether foreign-born musicians could compete with their American counterparts (he answered in the affirmative—in a roundabout manner) and the effect of alcohol and narcotics on a musician’s playing (he was emphatically against them). When he was asked if jazz would lose its sense of fun once it transformed into a kind of protest music, according to Down Beat, he had a cogent, pointed answer: “Jazz is supposed to run the gamut of all human experiences—anger, laughter, fun, and sadness.”

At the time, the arch-conservative John Birch Society was on the rise. And Gillespie’s candidacy, in its way, was an attempt to push back on both the political establishment and the rise of divisive forces in American life. Indeed, instead of decrying the far right, the ever inclusive Gillespie admitted to being open to considering a “John Bircher” in his Cabinet. “You see,” he said, “We’d need opposition.” At another point during the campaign, his followers began calling themselves “The John Birks Society”—as both a counterweight to conservatism and a coded reference to his own given name.

In the aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, Gillespie’s campaign went quiet for a period, apparently sensing that it was not the right moment to have fun with a run for the presidency. Even so, he was back on the trail as the ’64 election loomed closer. That September, he once again turned his set at Monterey into a mock political rally. During the height of the campaign, Gillespie enlisted jazz lyricist and vocalist Jon Hendricks to help him repurpose his classic tune “Salt Peanuts” into a campaign song, much as Frank Sinatra had done for John F. Kennedy in 1960 with “High Hopes.” The new lyrics went:

Your politics ought to be a groovier thing.

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

So get a good president who’s willing to swing.

Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!

In a typically comic Gillespie gesture, he even began to suggest names for nominees to his Cabinet, though the proposed personnel changed slightly in different interviews. If elected president, he promised to name a drummer as his secretary of defense: Max Roach. His secretary of state? Duke Ellington. For secretary of labor: singer Peggy Lee. Director of the CIA: Miles Davis, who surely was an expert on secrecy. Other appointments were more humorous—comedian Phyllis Diller as his running mate—and more serious—Malcolm X as attorney general. (Malcolm X would himself be assassinated only a month after the 1965 inauguration.)

Among Gillespie’s other campaign promises was a pledge to allocate government funds for such civil rights organizations as CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In Rollins’s view: “It was a typical gag for him. It was a positive thing for Dizzy in his own mind. A joke, but not a joke. Dizzy was aware of the whole dynamic.”

The campaign essentially ended with the landslide reelection of Lyndon B. Johnson on November 3, 1964. And the cover of that week’s issue of Down Beat depicted Dizzy in full presidential regalia, with top hat, appearing to take the oath of office by swearing on a Bible.

In 1971, Gillespie announced he was running again. This time, he selected Muhammad Ali as his Secretary of State, declaring, “He has charisma and a sincerity about his actions and his demeanor that would go very well in foreign affairs.” Gillespie said he would eliminate all military alliances, pull out of Vietnam at once, and instigate worldwide disarmament. He also advocated to begin a program to teach jazz in all American high schools. (During both runs, he made one additional campaign promise: He would rename the White House “The Blues House.”)

To many music fans these days, Dizzy Gillespie is hardly a household name. If it is familiar, though, it may be partly due to a decision by jazz impresario Wynton Marsalis, the artistic director of Manhattan’s Jazz at Lincoln Center, to christen the venue’s showcase nightspot Dizzy’s Club. Insists Dizzy’s manager, Roland Chassagne, the name was meant “to honor not only Gillespie’s groundbreaking contributions to the music but also the enduring impact of his legacy” as a way of keeping “Dizzy’s spirit alive nightly for future generations of musicians and fans.”

Though the spirit of Dizzy Gillespie thrives, the memories of his quixotic presidential campaign have nonetheless faded with the years. Even so, elders like Sonny Rollins recall the effort fondly, along with his old friend’s sense of mission: “I appreciated his undertaking that campaign—whether or not it was a gimmick or a serious look at life in the United States.” In these polarized times, the political process could use a little levity, some healthy outreach, and perhaps a common theme that might begin to bring us closer together.

As Dizzy advised:

Your politics ought to be a groovier thing.

So get a good president who’s willing to swing.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

September Cover Star Jenna Ortega Is Settling Into Fame

Republicans Think Trump Is Having a “Nervous Breakdown” Over Kamala Harris

Exclusive: How Saturday Night Captures SNL’s Wild Opening Night

Friends, Costars, and More Remember the “Extraordinary” Robin Williams

Tom Girardi and the Real Housewives Trial of the Century

Donald Trump Is Already Causing New Headaches in the Hamptons

Listen Now: VF’s DYNASTY Podcast Explores the Royals’ Most Challenging Year