In 1770, the wedding reception of Marie Antoinette and the dauphin inaugurated the frescoed and gilded Royal Opera at the Palace of Versailles—then the largest performance venue in France—a decadent celebration of what turned out to be, for the French monarchy, the beginning of the end.

Just a powdered-and-perfumed hair over 200 years later, what photographer Bill Cunningham described in his diary as “the miniature blue, gold and pink opera house of carved wood” again served as backdrop to an occasion of glittering excess and cultural shift—a much-photographed unlikely interrogation of race and class, presented anew in Rizzoli’s The Battle of Versailles: The Fashion Showdown of 1973. Compiled by Mark Bozek, who became acquainted with Cunningham’s archives while making his 2018 feature documentary, The Times of Bill Cunningham, the book collects the shots by that beloved chronicler of American fashion, many of them previously unpublished, alongside those of his French counterpart and friend, Jean-Luce Huré. The collection offers a lively and multifaceted glimpse of the moment that, as model Pat Cleveland puts it in her introduction to the book, “the Americans captured fashion leadership from the city of Paris.”

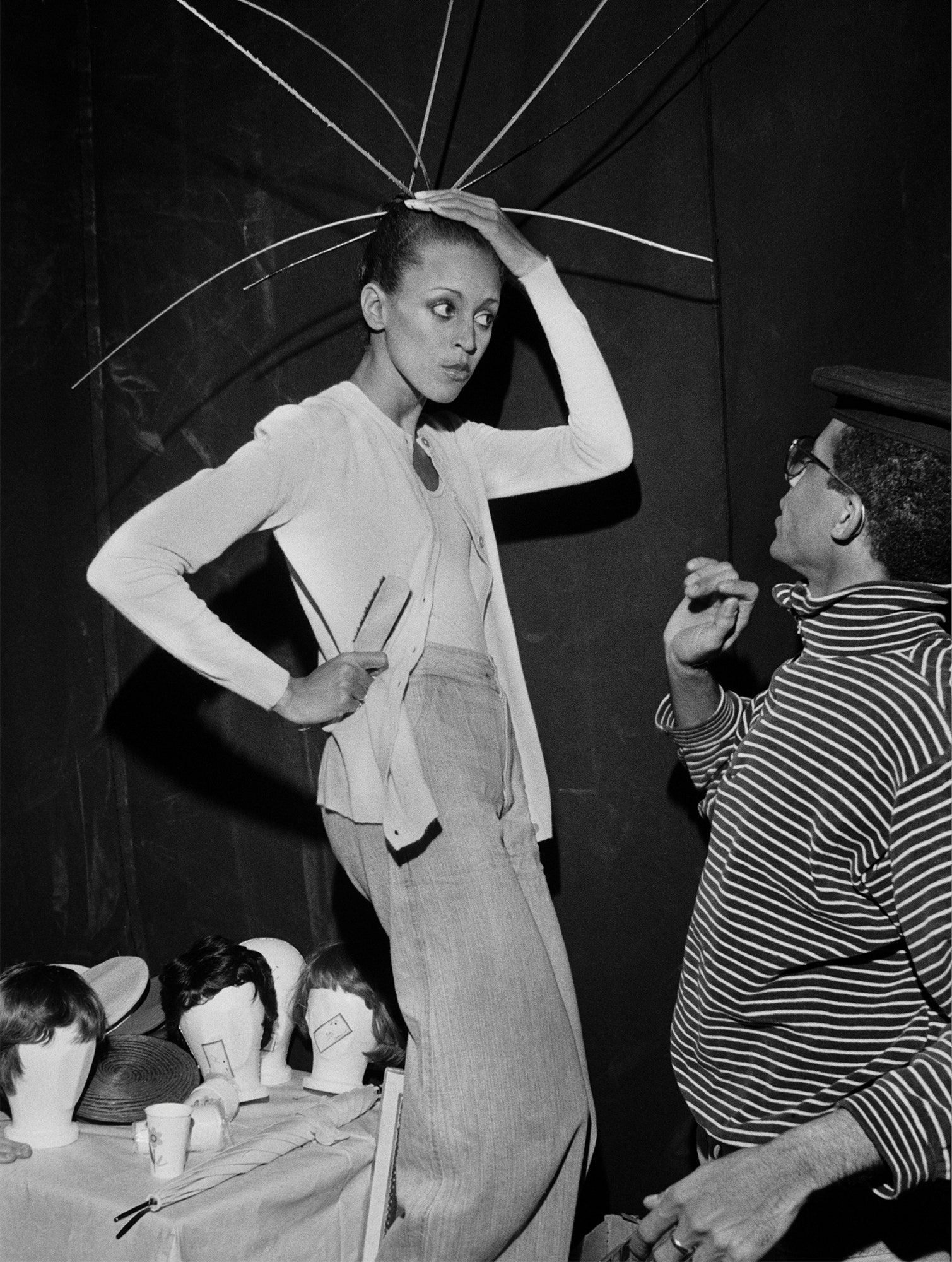

Cleveland was one of 36 models who arrived at Orly on the morning of Sunday, November 24, fresh-faced and punchy from JFK, and ready to compete in an opulent charity fashion show that would pit five French designers against five Americans. For the former, Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Cardin, Emanuel Ungaro, Marc Bohan for Christian Dior, and Hubert de Givenchy, with performances by Rudolf Nureyev, Jane Birkin, and Josephine Baker. For the latter, performances by Liza Minnelli bookended presentations by Oscar de la Renta, Stephen Burrows, Bill Blass, Anne Klein, and a volatile Halston (who, as the critic Robin Givhan recalled in her erudite and entertaining 2015 book on the occasion, had recently begun narrating himself in the third person and proceeded to yell “Halston is leaving!” as he crashed out of a rehearsal).

The pomp and personalities were ripe for Cunningham, whom Cleveland remembers as being “like Fellini with a still camera” and who referred to himself not as a photographer but rather a fashion historian. “Bill could charm you into wanting to have your picture taken, whether you felt like it or not!” Minnelli writes in her foreword to the book. “His photographs are poetry in motion, singing the symphony of the streets and the secret whisperings of the soirées.”

And what whisperings! In his diary, scanned pages of which appear in this collection, Cunningham describes the multiday event, from the models’ arrival—“they had zero awareness about the victory that was to come”—to the pregame celebration luncheon at Maxim’s and the postshow Hall of Mirrors dinner, at which “the great parquet floors were set with tables covered in 2,000 yards of specially woven royal blue cloth and fleur de lis,” the butter “molded into beehives with Napoleon’s signet royal bee spurting out of the top,” and the guests attended “by an army of servants, meticulously wigged and dressed in the 18th century tradition.” (“I wasn’t interested in food,” Cleveland notes. “I was too busy looking at the men in tights.”) Afterward, “the most aristocratic women were seen swirling over the parquet floors at 3:30 in the morning.”

But “as one’s memory shifted through the extravagant events, it was the scene of the fashion triumph”—the show, in the little gold opera house—“that lingered.” Cunningham recounts, with giddy disgust, the French designers’ overproduced numbers, with set designs that aspired to fairy tale but “turned out to be a poor imitation of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade,” culminating in a “rocket taking off into the ceiling with clouds of sparks and smoke, filling the beautiful auditorium and causing many of the exquisite to gag.”

The better to juxtapose the pared-down modernity of the Americans, who, thanks to ill-fitting sets, showcased their designs on an all-but-empty stage, opening on Minnelli’s rendition of “Bonjour Paris” as models and dancers swirled “in shades of beige and brown day clothes from each of the five designers.” It sparked “a love affair racing back and forth from the stage to the audience,” Cunningham wrote, and the models ran off the stage crying “They love us!” From that auspicious opening, the previously competitive American designers settled into “a spirit of family cooperation.” Notably, more than a quarter of the models were Black, with Cleveland starring in Klein’s segment, Billie Blair in de la Renta’s, and Bethann Hardison in Burrows’s class standout, in which formfitting jersey dresses and stripped ostrich feather headdresses brought down the house. As Cunningham wrote, “Everyone in the audience realized they were seeing something they had never seen before.”

Photographs reprinted from The Battle of Versailles by Mark Bozek, Rizzoli New York. Photos © Bill Cunningham.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

September Cover Star Jenna Ortega Is Settling Into Fame

Republicans Think Trump Is Having a “Nervous Breakdown” Over Kamala Harris

Exclusive: How Saturday Night Captures SNL’s Wild Opening Night

Friends, Costars, and More Remember the “Extraordinary” Robin Williams

Tom Girardi and the Real Housewives Trial of the Century

Donald Trump Is Already Causing New Headaches in the Hamptons

Listen Now: VF’s DYNASTY Podcast Explores the Royals’ Most Challenging Year