On New Year’s Day of 1841, Abraham Lincoln, then an Illinois state legislator, read a notice in the newspaper saying that his roommate of several years, Joshua Speed, was selling his Springfield general store and returning to his family home. Lincoln had not been previously informed of this. He would later refer to this day as “the fatal first of January,” one that sent him spiraling into a depression so profound he was put on a form of suicide watch. “I am now the most miserable man living,” he wrote in a letter. “If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth.”

The previous month, Lincoln had broken off his engagement to Mary Todd (whom he did eventually marry). This wasn’t his first documented expression of severe depression either. But in the new documentary Lover of Men: The Untold History of Abraham Lincoln (in select theaters September 6), experts argue that, despite these other factors, the source of Lincoln’s turmoil can be traced to his impending separation from Speed. Why? As historian Dr. Jean H. Baker (Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography) puts it, “His great love…was moving back to Kentucky.”

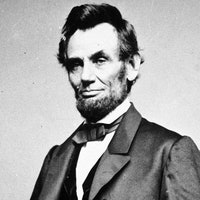

Over the last two decades, Abraham Lincoln’s sexuality has been feverishly debated in academic circles. Widely considered the greatest president in American history, Lincoln left behind a trove of detailed letters written to Speed that have met varying interpretations. His law partner and eventual biographer, William H. Herndon, collected letters about Lincoln, written by various acquaintances, that have also been reexamined as Lincoln’s potential queerness has come into focus.

Lover of Men, directed by Shaun Peterson (Living in Missouri) and produced by entrepreneur Robert Rosenheck, synthesizes these developments while making some contributions of its own, grouping more than a dozen prestigious scholars and historians to outline the case that Lincoln had sexual relationships with multiple men. “We are not trying to damage or besmirch or do anything harmful to Lincoln’s reputation—quite the opposite,” says historian Dr. Thomas Balcerski (author of Oxford University Press’s Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King). “We are broadening. We’re being more inclusive, and we’re taking a scholarly interpretation that has been bubbling up for generations—and that, finally in 2024, has found its moment to be expressed.”

Peterson became fascinated by the topic years ago, when he came across a provocative Gore Vidal essay in Vanity Fair titled, “Was Lincoln Bisexual?” Vidal assessed a groundbreaking book grappling with that theory: sex psychologist C.A. Tripp’s The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln (2005). He also contemplated Lincoln’s bond with Speed as sexual—thereby setting off what Peterson calls a “domino effect” in the academic world. One particular line in Carl Sandburg’s seminal 1926 Lincoln biography, The Prairie Years, seemed to take on an especially bold new meaning: The author described Speed and Lincoln’s friendship as containing a “streak of lavender, and spots soft as May violets.”

Harvard professor John Stauffer, a doctor of literary history, wrote the best-selling 2008 book, Giants, about the parallels between Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. “It suggested that Speed and Lincoln had carnal relations,” Dr. Stauffer tells me of his research.

Following the book’s publication, Stauffer was sharply criticized by many of his peers for his argument. “Virtually everyone sees Lincoln as an American icon, a great American figure—so if someone who is deeply prejudiced against gay or bisexual [people] sees someone writing a book saying that Lincoln is gay, that really ruffles their feathers,” he says. “[Herman] Melville and [Walt] Whitman had long been accepted as gay—and they’re major figures as well. But they’re not Lincoln.”

Lover of Men pinpoints Lincoln’s relationship with four men, from his early 20s to his presidency later in life: Billy Greene, a coworker in a general store; Elmer Ellsworth, an army officer and close friend; David Derickson, Lincoln’s bodyguard during the Civil War; and, most centrally, Joshua Speed. Peterson and the film’s featured scholars have not acquired any explicit evidence of sexual activity. But by exploring these bonds from a range of sociohistorical angles, they present their cases with conviction. The implicit question posed by the documentary, taking its evidence in totality: Why would you assume that Lincoln didn’t sleep with men?

Skeptics point to the customs surrounding living arrangements in the 19th century. Men of that era frequently, publicly slept in the same bed together as a means of convenience or money-saving. Yet as a new wave of historians argue, the knowledge of this practice has stood in the way of exploring that dynamic’s more multifaceted implications. “What’s been problematic is the gate-keeping that’s surrounded Lincoln historiography by august generations of Lincoln scholars,” Dr. Balcerski says. The sexual mores of the period weren’t so simple: While public romances between men were forbidden, the private realm wasn’t quite so surveilled. “When people say, ‘Oh, it’s impossible that the words homosexual and heterosexual were not widely used back then, that doesn’t make any sense,’ I’m like, ‘Well, just look at what’s changed in the past 20 years,’” says Dr. Lisa Diamond, a professor of psychology at the University of Utah. “In many ways, Western culture has defined being a man as being not homosexual. It’s really Lincoln’s image as a man that people feel is threatened by this intimacy.”

When Lincoln was in his early 20s, he and Greene slept together each night in a very small cot. Around this time in his life, family members and other acquaintances had, in writing, noted Lincoln’s particular disinterest in women—observations that Peterson saw for himself at the Library of Congress as he compiled research for the movie. Based on the record of the dynamic between Lincoln and Greene, “There almost certainly was the option to not share the cot,” Dr. Balcerski argues in Lover of Men. “Lincoln chose to sleep in this way.” Tripp had also plucked out a particular comment that Greene wrote of Lincoln that raised some eyebrows: “His thighs were as perfect as a human being could be.”

“A white, heterosexual, older scholar might just be like, ‘That’s kind of weird,’ and move on,” Peterson says. “But a sex researcher trained by Kinsey would say, ‘Oh, there’s something there.’”

Lincoln’s subsequent arrangement with Speed was similar. The future president had arrived in Springfield essentially penniless; the conventional wisdom is that he roomed with Speed because it was all he could afford. But Lincoln lived with Speed for far longer than a financial mandate would dictate, given his professional rise in politics and law during that period. “They slept in the same bed for four years, long after both men could have gone on their own—and they didn’t,” Stauffer says. Lover of Men presents several examples of their unusual closeness, including a letter to Lincoln written by his friend William Butler, offering the future president his own room and board. Lincoln chose to stay with Speed instead.

The film also focuses on the quality of Lincoln’s letters to Speed—which are far more intimate and raw than what he’d write to others. Lincoln signed some of his notes to Speed, “Yours forever.” He did not do the same for Mary Todd. “You feel the emotion on the page,” historian Dr. Michael Chesson says in the film. “Lincoln bares his heart with Speed in a way he doesn’t with other people.”

They stayed in touch following their aforementioned separation, as Lincoln reignited his engagement to Mary Todd and Speed himself got married. Immediately after his wedding, Speed wrote to Lincoln. “He consummated his marriage, and the first thing he wanted to do was to tell Abraham Lincoln that the sky didn’t fall,” psychoanalyst Dr. Charles Strozier says in the movie. In his reply to Speed, Lincoln described himself as utterly shaken by the news, unable to calm down. “For 10 hours after he reads of Speed’s successful consummation of his marriage, he’s shaking,” Strozier continues. “10 hours! This is a 33-year-old man.”

In his 2016 book Your Friend Forever, A. Lincoln: The Enduring Friendship of Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Speed, Dr. Strozier came to the conclusion that the relationship between Lincoln and Speed was loving but not sexual. “I can assure you I have not changed my mind,” he tells me now. “I was also impressed by Shaun’s determined effort to get on top of the literature, his questions of me during his research, and his several hours of interviewing me on camera. He disagreed with me, but made a serious effort to understand my argument.”

Scenes between Lincoln and his alleged sexual partners play out in Lover of Men as silent reenactments. The structure is maintained through the documentary’s final act, when President Lincoln begins an affair with his bodyguard. “I didn’t want to make the recreations over-the-top, where they were making out and stuff—I wanted them to be loving,” Peterson says. “It’s a powerful image to see President Lincoln, with the beard, in bed with his bodyguard.” Dr. Diamond finds the approach appropriately affectionate: “We want our leaders to be capable of depth and love and warmth and intimacy and friendship,” she says. “The idea that that could take someone’s standing down [reflects] the upside-down world that we live in.”

Before depicting Lincoln and Derickson’s affair during the Civil War, Peterson had a particularly juicy visual aide ready to go, one documented in the historical record: Derickson wore Lincoln’s clothes. As his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Chamberlain, wrote in the regimental history, “Captain Derickson advanced so far in the president’s confidence and esteem that, in Mrs. Lincoln’s absence, he frequently spent the night in his cottage, sleeping in the same bed with him, and, it is said, making use of his Excellency’s night-shirts!” Dr. Chesson highlights this moment in the film as becoming “the talk of Washington DC.” No kidding.

As Peterson began assembling Lover of Men during the pandemic, he realized the timeliness of the project. For young adults today, strict sexual categories are going back out of style. “These concepts, ideas, behaviors, and categories did not exist in Lincoln’s time…. People were very fluid in the past. Lincoln was very fluid, certainly,” he says. “I feel like Gen Z might just take the baton back from the old days and continue the way humans always were.” Stauffer has his Harvard students read letters between Lincoln and Speed without telling them what to think. “When they do, it doesn’t matter whether that student is a conservative or a radical liberal—it’s profoundly illuminating for them,” he says. “It’s empowering.”

Since the release of its trailer, Lover of Men has been thrust into the social-media culture wars. The likes of Ben Shapiro and Alex Jones have reacted mockingly, leading some of their followers to do the same. Several scholars remain firm that the evidence does not suggest Lincoln engaged in sexual activity with men, and will likely counter the documentary’s claims once more when it’s out in the world. But a narratively driven argument of this scale, backed by so much research and interwoven scholarship, marks new territory for the subject. “I would ask those guys to watch the film, give it a chance, look at the evidence—because it’s pretty compelling,” Peterson says. “I’m still learning this as I go along too.”

Dr. Balcerski first started investigating this topic in graduate school, where he studied larger patterns of male friendships and relationships in the 19th century. He arrived at the notion of a “gay Lincoln” highly skeptical, like so many before him. But the material, he believes, speaks for itself. He read folks like Tripp and Stauffer to inform his own pioneering work in the space.

“I’m in some ways late to the game to understand this, but I also might’ve been among the first group of people who finally had a rich body of literature they could pick up on their library shelf or in a database that actually makes this argument about Lincoln’s sexuality in a way legitimized by our fields,” he says. “I think now we will see it accepted as a legitimate argument, one that deserves further research attention.”

“There’s never been a movie, ever, on this topic,” Peterson adds. “You would hope that a young person out there is going to see the visuals of this and be inspired to take the torch and get deeper into Lincoln’s letters and Lincoln’s history.” If there’s one takeaway from Lover of Men, it’s that when it comes to Lincoln’s love life, there’s a whole lot more to know.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

September Cover Star Jenna Ortega Is Settling Into Fame

Republicans Think Trump Is Having a “Nervous Breakdown” Over Kamala Harris

Exclusive: How Saturday Night Captures SNL’s Wild Opening Night

Friends, Costars, and More Remember the “Extraordinary” Robin Williams

Tom Girardi and the Real Housewives Trial of the Century

Donald Trump Is Already Causing New Headaches in the Hamptons

Listen Now: VF’s DYNASTY Podcast Explores the Royals’ Most Challenging Year